SPEAR Lab Focus

Jump to: SPEAR Lab & Existential Psychology | Freedom & Authenticity | Death & Self-Determination | Culture & Politics | Religion & Atheism | Physical Health & Well-Being | Trauma & Mental Health

One of the most exciting aspects of psychological science is the challenge of grappling with “big” questions about why we humans do what we do. Why do we contribute to our communities, create art, build hospitals, teach students, start businesses, play sports, raise families, fight wars, strive toward peace? Why do we believe in souls, gods, and afterlives? Why do we worry about whether we’re being our “true,” authentic selves?

Upper: Works such as Grimm’s Fairy Tales, the Bible, The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, and J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings each explore themes surrounding death, freedom, character, truth, and purpose.

Lower: Existentialist philosophers Soren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Certainly, those big questions have been the focus of many of humankind’s richest studies of ourselves and the world around us: religious teachings and scriptures the world over, epics from Gilgamesh to Tolkien, meditations from Confucius to Aurelius, poems and songs from Omar Khayyam to Bob Dylan, and even the moralistic folk tales, fables, and parables of Aesop and The Brothers Grimm. These and mountains of others represent some impressive efforts to better understand the human condition and collectively equip ourselves for a brighter future.

Adding to this chorus, philosophers such as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Sartre, among many others, turned their focus more directly on the challenges of “being” and “becoming”—of choosing what to do, who to be, why, and how. But in contrast to most of the previously accumulated wisdom, the existentialist philosophers rejected the ideas that the world was inherently meaningful and that we humans are here to fulfill any particular purpose. Instead, they identified several unique psychological capacities that enable humans to grapple with the challenge of authentic living in a world where we know that we die, and where meaning and purpose are often little more than arbitrary human constructions.

A full look at the human experience, in light of these critical existential perspectives, has the potential to better inform our understanding of our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and even the broader cultural systems that set the stage for our day-to-day lives.

SPEAR Lab & Existential Psychology

In the Social Psychology & Existential Attitudes Research (SPEAR) Lab, we study the role of core issues of “being” and “becoming” in social and mental functioning, including:

Concerns about life and death, and the awareness of mortality;

Self-determination and the challenges of authentic and inauthentic choices/actions;

Experiential isolation and a sense of shared reality;

Culture, self, and identity;

The struggle for meaning and purpose in life;

Religion and spirituality; and

Occasions for adjustments and opportunities for personal growth.

We apply the contemporary methods of modern psychological science to systematically explore the role of these existential concerns in a variety of ways.

Primary/original data collection. Our research questions often involve ideas that have not yet been directly explored in any previously existing data. In those cases, we design our own studies and collect original data ourselves. Occasionally our studies gather holistic descriptions of particular experiences using qualitative methods. But most often we use quantitative methods to document systematic relationships between two or more phenomena. Sometimes we use correlational studies to measure whether one variable might be systematically associated with another; sometimes we use longitudinal studies to track changes over time (e.g., before, during, and after an election) or across parts of the lifespan (e.g., young, middle, and late adulthood); and sometimes we use experimental study designs, in which we intentionally manipulate a particular social or mental variable, to observe the causal impact on various psychological processes and social functioning.

Secondary data collection. Sometimes our research questions involve ideas that have been directly addressed in previously reported and publicly available data. For example, several previous studies might have each used a similar design, and we might ask: Did those studies find a consistent pattern? In those cases, we might do a systematic review of the literature, gather and code previously reported data, and conduct a meta-analysis—an analysis of prior analyses, looking for patterns in the accumulated body of data.

Freedom & Authenticity

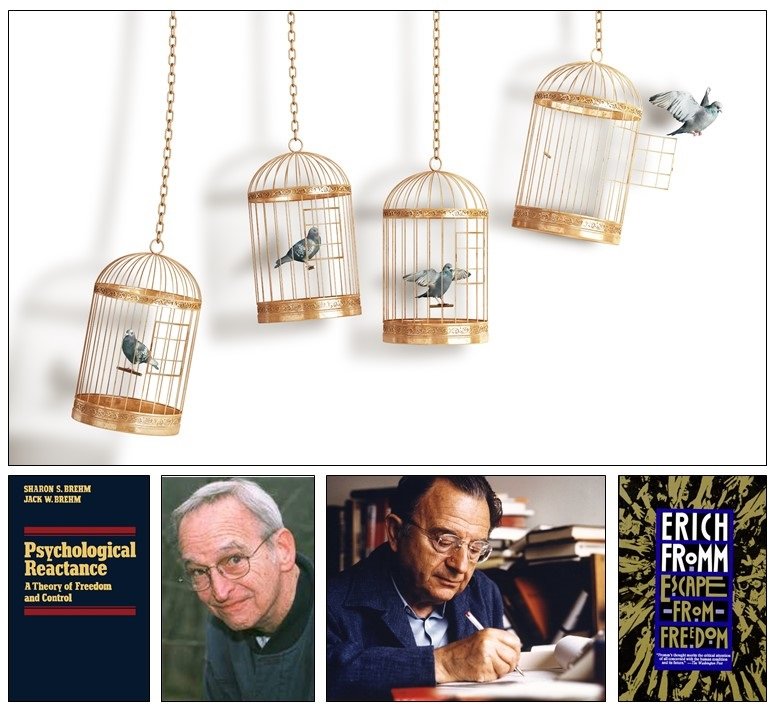

Sometimes we can’t wait to break free of our cages, yet sometimes the same features that limit us can provide protection and comfort. Lower row: Psychological Reactance (1981); researcher Jack Brehm; philosopher Erich Fromm; Escape from Freedom (1941)

Psychological science has learned much about the importance of freedom and authenticity. People who perceive restrictions on their freedom will push back to reassert their agency (e.g., reactance theory). And experiencing authenticity—feeling that one’s actions are an expression of one’s own free will, rather than some external pressure—leads to better performance and engagement in a wide variety of life domains (school, work, close relationships) and facilitates better physical and mental well-being.

But on the other side of that coin, existential psychology also explores the consequences of being faced with the “burden” of freedom. Various theoretical perspectives suggest people may sometimes experience decision fatigue and/or anxiety due to the options and uncertainties that can come with the fundamental freedom to choose who to be, what to do, why, and how. As a result, people may take steps to reduce their freedom, thereby reducing its psychological burden. For example, some people may seek to reduce their decisional options by deferring choices to social norms or preferring autocratic leaders (e.g., gov’t officials, employers, parents) who make decisions on the followers’ behalf rather than democratic leaders who involve the followers in the decision-making process. Thus, experiencing freedom may sometimes entail ironic consequences, posing a motivational obstacle to the expression of one’s own free will and to social participation in democratic systems large and small.

Death & Self-Determination

Our research has tested some of the core ideas from Martin Heidegger’s principal work, Being and Time (1927), finding that the awareness of mortality is what helps orient us toward authenticity.

A central theme in much of existential philosophy is the idea that a limited timeframe, which comes with the awareness of mortality, is what orients us to engage our freedom in the first place—motivating us to want to be our most authentic self in any given moment. There are seemingly infinite ways of being in the world; countless career paths to join, clothing styles to adopt, people to befriend, and so on. If we knew we had unlimited time, we wouldn’t have to choose—we could engage in all of them. But we know that our time is limited, we know we’re mortal—and so we can only engage with a few of them. Thus, the question is whether we allow our life path to be shaped by external forces (parents, employers, cultural norms) or whether we make our own self-determined choices as an authentic expression of ourselves.

One stream of our research has been exploring this issue in systematic ways. Some of our studies investigate whether the awareness of mortality can motivate people toward more authentic living. Some of our other work asks whether reduced autonomy leaves people vulnerable to death-related existential concerns, and whether experiencing self-determination might mitigate those death-related concerns and maintain well-being. We also study whether, for people who feel a strong sense of self-determination, death-related concerns might motivate personal growth and an interest in social, intellectual, and cultural exploration.

Culture & Politics

One existential motivational perspective posits humans’ sophisticated awareness of death motivates a constellation of affective, cognitive, and sociocultural processes, designed to facilitate the perception that one is valued member of a cultural system offering some form of death-denying permanence (e.g., scientific medical advances, supernatural afterlife, or some other secular legacy via work, art, sports, education, government, child-rearing, etc.). From this perspective, we can begin to better understand why people are so invested in their cultural abstractions, and so fervently pursue related cultural goals—because they offer a psychological sense of permanence in the face of the physical reality of our impermanence.

Our research in this area has focused on better understanding both the “dark side” and the “light side” of death-related existential concerns—touching on a wide range of cultural and political topics:

Closed-mindedness, ideological dogmatism

Prejudice (racial/ethnic, nationalist, and religious)

Presidential voting preferences

Foreign policy (military action, diplomacy, peace)

Domestic policy (immigration, religious freedom)

Prosocial values (tolerance, compassion)

Open-mindedness, personal growth, and well-being

Religion & Atheism

Another stream of our research explores how death-related existential concerns can potentially lead to expressions of religious faith under some conditions—but not others. Research finds that religious beliefs are particularly well suited to mitigate death anxiety via belief in afterlife, supernatural agency, human ascension from nature, and spiritual distinctions between mind and body. Indeed, the fact that—historically—the majority of people worldwide are religious is a compelling statement about the likely role of existential motivation to maintain religious faith. But also interesting is the fact that—in the modern era—the number of non-religious, agnostics, and atheists has been steadily growing. Thus, our lab not only seeks to better understand the roots and motivations of religious belief but also to explore whether and how skeptics’ rejection of such an intuitive and powerful death-denying worldview might impair well-being and/or require skeptics to adopt a more open-minded/growth-oriented approach to alternative (secular) cultural meaning systems.

Physical Health & Well-Being

Existential psychology research shows there is reason to expect that when mortality concerns are in conscious attention, people try to reduce the perceived threat, either by taking steps toward good health (e.g., wearing a seatbelt in the car, sunscreen at the beach) or by denying their vulnerability (if taking steps toward good health is difficult, such as with nicotine addiction). But when mortality concerns are cognitively accessible, yet non-conscious, people manage those concerns by seeking a symbolic sense of permanence by adhering to salient cultural standards of worth.

We’ve explored the implications of these processes in a variety of domains. We’ve contributed to research studying the impact of existential concerns on actual cigarette smoking behavior during cravings. We’ve also investigated how both conscious and non-conscious death-related concerns impact the effectiveness of communications promoting actionable health-relevant behaviors, such as smoking cessation, seasonal influenza vaccination, responsible alcohol consumption, and healthy food shopping behaviors. Indeed, tailoring public health messages to relevant existential concerns is a critical vehicle for effectively promoting good health behavior.

Trauma & Mental Health

We’ve also been exploring the idea that traumatic events (natural disasters, assault, abuse, war and political violence, life-threatening medical events, and so on) might disrupt people’s existential-anxiety-buffering worldviews. Such traumatic stressors vividly demonstrate that, despite successfully living up to our standards and values, the world remains a dangerous and chaotic place, and our symbolic cultural activities do little or nothing to protect against the harsh reality of our inevitable and unpredictable mortality.

This stream of research explores whether posttraumatic stress may reflect, in part, an impaired ability to rely on one’s previously-intact worldview beliefs to manage existential concerns about death. Indeed, some of our studies have found that people with low posttraumatic stress were effectively protected against increased death-thoughts and anxieties when they affirmed their cultural beliefs; but those with high posttraumatic stress (above the pre-diagnostic threshold for PTSD) were not, suggesting that their belief systems were no longer effectively functioning as protections against existential anxiety.

Our ongoing research may further explore some of the fascinating implications of these findings for personal growth, as people with posttraumatic stress might respond well to death-awareness by making an open-minded search for alternative belief systems instead of relying on their extant yet ineffective belief systems. Such a response might potentially result in a growth-oriented exploration of novel ideas, people, and experiences that could help restore some sense of existential security, promote a sense of meaning and purpose, and help restore the individuals’ mental health.